While Charlie has always been interested in electronics (he’s even written “a book. “Whenever money came my way, I caused it to disappear,” he laments, blaming his weakness for “schemes, semi-legal ruses, cunning shortcuts.” He resides in the south of London, gets by “playing the stock and currency markets online,” and lives in “genteel ruin.” When Charlie inherits a lot of money after his mother’s death, he spends way too much of it-86,000 pounds-on Adam. His subsequent scientific tours de force-in the novel-have contributed to the creation of Adam.Īs the novel commences, Charlie is a middle-class ne’er-do-well who, at the age of thirty-two, is completely broke. Turing was-in real life and in this book-instrumental in helping the Allies win World War II through his successful efforts to “read” the codes produced by Nazi Germany’s infernally difficult-to-crack Enigma machine. Withal, the most relevant rewritten-history aspect is that Alan Turing, the great computer scientist, didn’t commit suicide after World War II because of societal opprobrium prompted by his homosexuality. I must say at this point that I don’t believe the alternate-universe trappings add anything to the book’s themes. Then he’s assassinated by the Irish Republican Army. The new prime minister is Tony Benn (in real life, an MP for forty-seven years), who (at least in this book) is charismatic, popular, and eager to implement a far-left agenda in a very bedeviled Britain. Britain has lost the Falklands War with Argentina and suffered too many horrible casualties, and so disgraced Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and her Tories lose a Parliamentary election to Labour. Kennedy and John Lennon have not been murdered and the Beatles have reassembled.

Machines Like Me takes place in the United Kingdom but in what I believe science fiction buffs call an alternate universe. At one point he tosses off three-artificial human, android, replicate-and at another, he angrily uses “ambulant laptop.” (Even terminology becomes surly.) I like the latter, but for simplicity’s sake, I’ll stick with android.

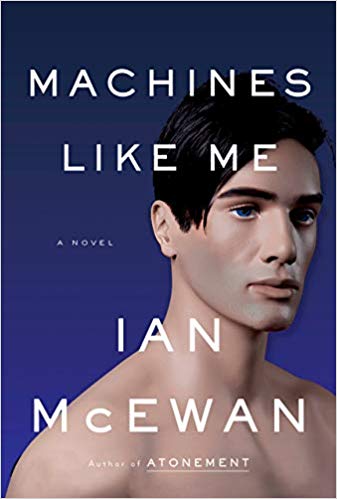

what? Charlie, the narrator-protagonist of the novel, can’t settle on one descriptive term for Adam, his new state-of-the-art sidekick. And so prepare yourself for Adam, the star of Machines Like Me. Surely if a very good, perhaps major, novelist ( Amsterdam, Atonement, et al.) can’t make sense of that question, there is value in observing him wrestle with the subject. The ultimate result, I’m sorry to say, is a peculiar and largely unsatisfying book. Early on in this novel, the momentous question it raises-what is a human being?-becomes maddeningly opaque, and the anguished vibes that pervade Machines Like Me indicate that Ian McEwan isn’t pleased that he can’t delineate more profound answers.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)